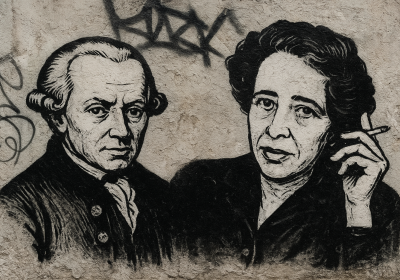

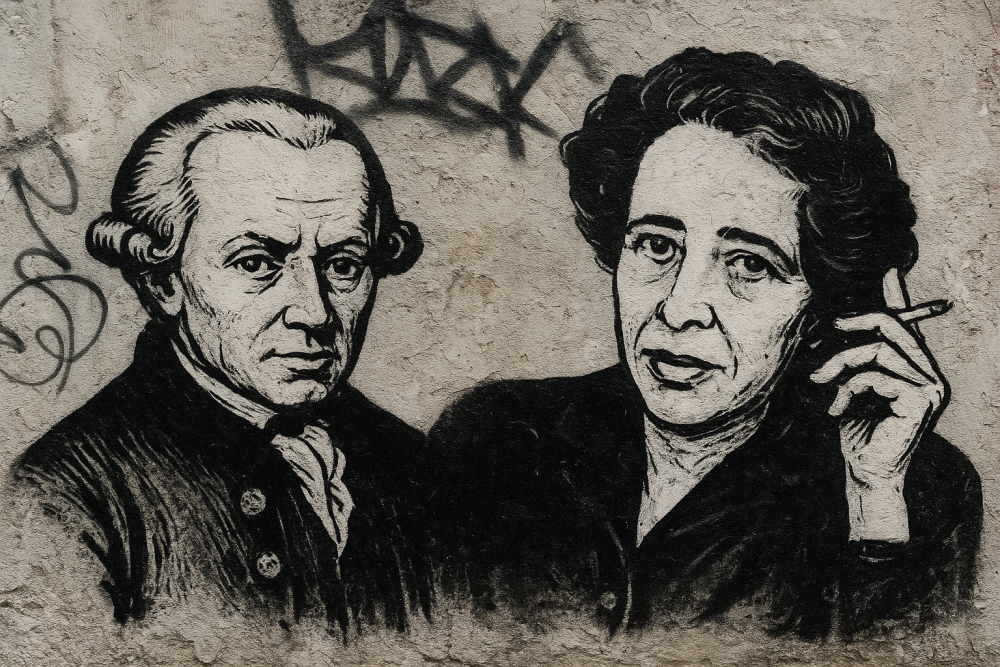

In any courtroom, the act of judgment is often imagined as the purest expression of reason — a calm weighing of evidence, untouched by emotion or bias. Yet philosophy has long warned us that judgment is never so simple. Immanuel Kant, the eighteenth-century philosopher who redefined the modern mind, believed that judgment was the bridge between knowledge and morality: the space where our capacity to understand the world meets our ability to act rightly within it.

In The Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant describes judgment as a delicate balance between sense and understanding. To judge fairly, he wrote, one must not rely on feeling alone — for feelings are private and fleeting — but neither should one depend solely on cold reason, which risks becoming detached from humanity. True judgment, in his view, arises when we bring together the clarity of reason with what he called the sensus communis, the shared sense of humanity that allows us to imagine the standpoint of others.

For Kant, the ideal judge is one who can think “enlargedly” — to place herself in the position of every other rational being before reaching a verdict. It is an ethical ideal, grounded in the hope that human reason can transcend prejudice. The courtroom, in this sense, becomes a small model of the Enlightenment dream: that justice could emerge from rational dialogue, free from dogma or passion.

But in the twentieth century, Hannah Arendt returned to Kant’s ideas and quietly broke that dream apart. Arendt admired Kant more than almost any other philosopher, yet she recognized that his faith in the universality of reason was too pure, too hopeful for the messy world of politics and history.

In her essays collected in Between Past and Future and in her posthumously published Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy, Arendt argued that prejudice cannot be erased — it is the very soil from which judgment grows. Every act of judgment, she insisted, is shaped by the culture, language, and moral traditions we inherit. Even the most rational decision is formed within a web of assumptions that precede our conscious thought.

That doesn’t mean, for Arendt, that judgment is doomed to be unjust. Rather, it means that justice begins not with the fantasy of neutrality, but with the awareness of our own partiality. The task of the judge — or of any thinking citizen — is not to purge prejudice, but to confront it, question it, and keep it open to dialogue. “Thinking without a banister,” as Arendt famously put it, means judging without the comfort of absolute laws — walking through the world without a fixed railing to hold on to, but with the courage to think for oneself in the company of others.

This view feels particularly relevant in societies where moral law and civic law are tightly bound — where religious or cultural values define not only what is legal but what is thinkable. Across much of the Middle East, judicial systems face the challenge of modernization while standing on centuries of moral tradition. Judges, often raised in deeply religious or conservative environments, are expected to interpret new laws of freedom, expression, or gender equality through lenses that were shaped long before such concepts were imaginable.

Kant might have hoped that the rational application of law could ensure fairness in these settings — that reason, properly cultivated, would rise above local prejudice. Arendt would have warned otherwise. She would say that the very notion of “reason” in such a society already carries its own history, its own set of silent assumptions. The law itself is not neutral; it reflects the values of those who wrote it, and the prejudices of those who enforce it.

The real hope, then, lies not in creating judges who are free from bias — a philosophical impossibility — but in nurturing judges who are conscious of their biases. Awareness becomes the new form of virtue. Dialogue, rather than purity, becomes the test of justice.

In this light, the most radical act in a court of law may not be the verdict itself, but the moment of reflection before it — the pause in which a judge recognizes that her sense of what is right has been shaped by her own world, and that someone else’s world may see it differently. That pause, fragile as it is, may be the closest thing to justice we have

Leave a Reply